Summary

Fibrous dysplasia is an uncommon, benign disorder characterized by a tumor-like proliferation of fibro-osseous tissue. The cause of fibrous dysplasia is unknown. It may either present as monostoic, affecting one bone, or polystoic, affecting many bones. Fibrous dysplasia is usually found in the proximal femur, tibia, humerus, ribs, and craniofacial bones in decreasing order of incidence.Polyostotic cases can affect multiple adjacent bones or multiple extremities.

Complete Information on this Tumor

Fibrous dysplasia is an uncommon, benign disorder characterized by a tumor-like proliferation of fibro-osseous tissue. The cause of fibrous dysplasia is unknown. Most cases of fibrous dysplasia display no particular pattern of inheritance. Fibrous dysplasia can present as an autosomal dominant disorder affecting the mandible and maxilla bones in children in their teenage years.

The tissue in the tumor is immature, woven bone that cannot differentiate in to mature, lamellar bone. This may be due to a mutation in a cell surface protein. There may be a relationship between the c-fos proto-oncogene and the development of fibrous dysplasia. This is a somatic mutation, rather than in the germline. The abnormality is limited to the tissues within the lesions. The cells have an increased number of hormone receptors, which may explain why these lesions become more active during pregnancy. This author has seen patients who have increased pain in their fibrous dysplasia lesions linked to their monthly menstrual cycle.

Also, polystotic fibrous dysplasia is known to have multiple associations with other disorders. The combination of polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, precocious puberty, and cafe au lait spots is called Albright's syndrome. The association of fibrous dysplasia and soft tissue tumors has been given the name Mazabraud's syndrome. Other endocrine abnormalities including hyperthyroidism, Cushing's disease, thyromegaly, hypophosphatemia, and hyperprolactinemia have been associated with fibrous dysplasia.

Most patients are diagnosed with fibrous dysplasia in the first three decades of life. Cases of polyostotic fibrous dysplasia are typically diagnosed in the first decade of life. Females and males are equally affected.

Fibrous dysplasia can occur anywhere but is usually found in the proximal femur, tibia, humerus, ribs, and craniofacial bones in decreasing order of incidence. Skeletal deformities can occur as a result of repeated pathological fractures through affected bone. Polyostotic cases can affect multiple adjacent bones or multiple extremities.

Monostotic fibrous dysplasia may be completely asymptomatic and is often an incidental finding on x-ray. Pain and swelling at the site of the lesion can also be present. Female patients may have increased symptoms during pregnancy. Unfortunately, this tumor can also present as a pathological fracture that is followed by a nonunion or malunion.

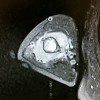

T-99 bone scan uptake may be normal or increased. Bone scans are not helpful in diagnosing these lesions but can be useful in identifying asymptomatic lesions. MRI scans or CT scans can be helpful in delineating the extent of the lesion and identifying possible pathological fractures. Sarcomatous change within the lesion can be identified by MRI or CT scans.

Surgery with curettage of the lesion can be associated with high rates of local recurrence. Painful long bone lesions can be stabilized by cortical grafting or implant fixation. Cortical strut grafts are preferred to a morselized cortical cancellous grafts, which can become replaced with the same immature fibrous lamellar bone that comprised the lesion. Curettage and bone grafting alone is best suited to lesions in non-weight bearing bones.

Lesions within the proximal femur are a particular challenge because they present in the young patients, and complications of treatment or from the tumor can lead to significant damage to the affected hip joint and long-term disability. These lesions should be evaluated carefully for risk of pathological fracture. It is the author's opinion that rigid, intramedullary fixation with the strongest possible device (a steel or titanium cephalomedullary nail) is the best method for treatment of proximal femoral lesions.

The authors feel that patients with symptomatic or large lesions from fibrous dysplasia should be placed on biphosphate medicines long-term. These medicines have proven effective in reducing symptoms and increasing cortical thickness. The author uses Fosamax 35 mg weekly for children and 70 mg weekly for adults. Any patient with fibrous dysplasia who has had surgical stabilization should be placed on Fosamax post-operative. Review the indications and dosage for Fosamax before prescribing. The use of Fosamax in children is not routine and should be managed carefully and conjunction with an experienced pediatrician. Large, symptomatic or critical lesions can be managed with intravenous bisphosphonate medicines, including zolendronic acid.

Orthopedic pathology by Bullough, third edition, times mirror international publishers Ltd., London, 1997

Getelis et al, benign bone tumors. Instructional course lectures, 45: 426-46, 1991.

Huvos, Andrew bone tumors: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis WB Saunders Co., 1991

Parekh et al, fibrous dysplasia journal of the American Academy of orthopedic surgeons, volume 12, number five September/October 2004, page 305-313